From Ancient Times To Modern Days: A Brief History Of Indian Migration To Malaysia

Malaysian Indians make up about 7% of the current Malaysian population.

2,073,647. That's the number of Indians in Malaysia as of June 2017.

Malaysian Indians are the fourth largest ethnic group in the country and they make up about 7% of the Malaysian population.

Malaysian Indians are people with full or partial Indian descent, who were either born in Malaysia or have gained Malaysian citizenship. They can be considered as Person of Indian Origin (PIO) - people who are not citizens of India but have Indian ancestry, and are citizens of other countries.

Malaysia is the third country in the world with the largest population of overseas Indians. There are more than two million Indians living here currently, with some 200,000 Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) who are currently working and residing in Malaysia, concentrated in the IT industry.

NRIs are basically expats with an Indian passport who have emigrated for employment, residence, education, or any other purposes for a temporary period of time. They add up to the population of Indians in Malaysia, having established large communities in Kuala Lumpur, especially in Brickfields.

Over the years, Malaysian Indians have become an integral part of the local society.

But, how did it all begin - Why and how did Indians start migrating to Malaysia?

The migration of Indians to Malaysia came in four main streams, with most of it tied to different economic needs and roles, namely:

Note: The facts and details below were based on books and papers on Indian migration to the Malay Peninsula, mainly 'India's Diaspora Policy: A Case Study of Indians in Malaysia'.

1. Ancient times - The beginnings of Indian influence in Bujang Valley, Kedah

Ancient Indian influences in Malaysia dates back to around AD 110, when certain parts of pre-colonial Malaysia like Kadaram (Kedah) and the Malacca Sultanate (Melaka) were still part of the Greater India kingdoms.

Traces of Indian migration and civilisation can be seen in the Bujang Valley settlement believed to be the oldest civilisation in Southeast Asia influenced by ancient Indians.

The archaeological excavations at Bujang Valley, located near present day Merbok in Kedah, have revealed a wealth of relics and ruins, including Hindu icons, stone caskets, and tablets that may date back to more than 2,535 years ago.

These remains serve as a primary source of information for historians, highlighting the presence of a Hindu-Buddhist polity in the area.

2. Pre-colonial period - Expanding trade relations with the Malacca Sultanate

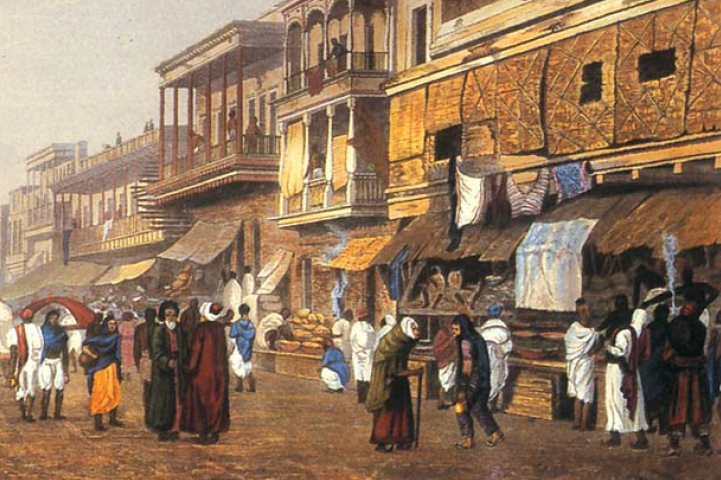

During this period, most of the contacts initiated by the Indians were for their own benefits, especially in terms of trade.

As the Malacca Sultanate grew to be one of the most powerful and strategic entrepôts of its time and became part of the ancient spice route in the 15th century, Indian traders flocked to the sultanate, looking for gold, spices, exotic local produce, and tin.

Some of the traders, including the Indian Muslim ones, stayed back and married locals. However, it is believed that the scale of Indian migration during this time was relatively small.

3. Colonial Period - The largest Indian migration to Malaysia

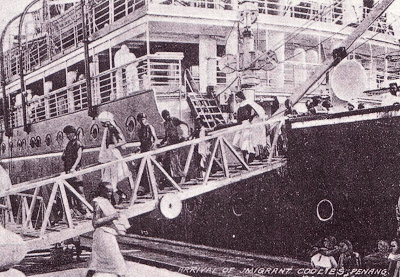

Indentured Indian workers arriving at a port in British Malaya.

Image via The Malaysian Indian Dilemma/Janakey Raman ManickamMost states in modern day Malaysia were under British Malaya, which was made up of the Straits Settlements, the Federated Malay States, and the Unfederated Malay States.

The colonial period was when the British were developing the economy of the states in British Malaya, increasing their revenue mostly via plantations, mining, and constructions. They also needed workers to fill in positions for the maintenance of transportation lines including roads and railways.

Meanwhile, by early 19th century, the British empire had expanded its control over almost all of pre-independence India, which include modern day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Indian workers were easily accessible and they were recruited to work in British Malaya, leading to what is probably the largest Indian migration to Malaysia.

There was an increased need to fill these positions with immigrants and South Indian workers, specifically Tamils and Telugus, as their wage rates were lower and they worked well under supervision.

In short, they were easy to maintain.

The English also recruited North Indians to fill up positions in the police force and security services, while the Malayalees and Jaffna Tamils were mostly employed in clerical and civil service.

During the British occupation, Indian merchants and the Chettiars were also making their way to British Malaya for trade and business opportunities.

The Chettiars were traditionally merchants and traders but they grew to be involved in and eventually led the banking and moneylending industry in South India.

Note: Straits Settlements was made up of four states, namely, Penang, Singapore, Melaka, and Labuan. The Federated Malay States were Selangor, Pahang, Perak, and Negeri Sembilan which had British Resident-Generals governing each state. As for the Unfederated Malay States - Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, and Terengganu - they were standalone British protectorates. It was only in 1948 that these three collection of states were grouped together to form the Federation of Malaya.

The largest and most significant migration of Indians to Malaysia was mainly during the colonial period.

Thousands of Indians were brought in as indentured (contract) workers to work in various plantations across British Malaya.

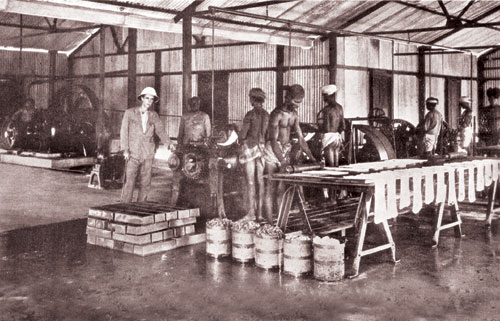

An undated photo of Indian workers in a rubber factory in Malaya.

Image via The Malaysian Indian Dilemma/Janakey Raman ManickamThe British Malaya states' climate and geography proved to be conducive for growing cash crops and when the British set foot and took over the states in the area, they developed large scale agricultural projects that proved to be very lucrative.

By late 1800s, these projects became an integral part of the international economy, supplying tin, sugar, coffee, and rubber. The rubber supplied by plantations in British Malaya were also in high demand due to the expansion of the automotive and electrical industries in the West.

In comes labour migration. Most of the labourers that first set foot in British Malaya came under the indenture system to work in sugarcane plantations, until rubber took over as one of the biggest agricultural ventures in British Malaya in late 1800s.

Rubber produced in British Malaya once supplied nearly half of the world’s rubber supply!

Labourers that came under the indenture system would typically work for the same employer for a period of five years, on fixed non-negotiable wages

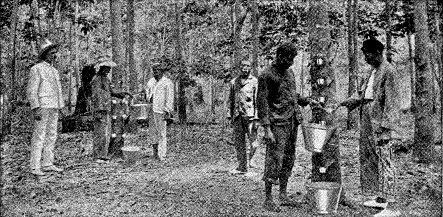

An undated photo of Indian labourers at a rubber plantations in British Malaya.

Image via iumwmalaysianstudies.blogspot.myThe indenture system is a form of debt-bondage where a prospective employer will place an order for the number of labourers he needs through recruiting agents in India. Once the contract ends, the labourers can be 're-indentured' or released from it.

Most of the labourers were supplied from Tamil Nadu. This is why almost 90% of the first batch of Indian labourers were Tamil-speaking South Indians.

These labourers were mainly from areas such as Thanjavur, Salem, Chingleput, Tiruchirappalli, and Ramnad in Tamil Nadu. The two main ports of departure were at Nagapattinam and Madras.

Occasionally, the Telugu districts in Andhra Pradesh and the Malayalam districts of Malabar also provided labourers.

In early 1900s, there was also demand for labourers to work in municipal services and for road and railway construction in British Malaya.

However, Indian labourers were more commonly hired to do monotonous, hard work in very harsh conditions.

According to Kernial Singh Sandhu in, 'Indians in Malaya-Immigration and Settlement 1786-1957', "The South Indian labourers were preferred because they were malleable, worked well under supervision, and were easily manageable. South Indians were not as ambitious as most of their northern Indian compatriots and certainly nothing like the Chinese... they were the most amenable to the comparatively lowly paid and rather regimented life of estates and government departments. South Indian had fewer qualms or religious susceptibilities and food taboos... and cost less in feeding and maintenance".

By early 20th century, more Indians started coming to British Malaya voluntarily, seeking greener pastures. This time around, there was a boom of young, educated Indians, especially Malayalees coming to the British colony.

Most of these young men who hail from states such as Travancore, Cochin, and other Malabar districts made their way to British Malaya starting from the 1920s. They migrated for clerical employment and slowly worked their way up the government sector. This was the start of educated Indian Tamils' migration to British Malaya.

In addition to the Malayalees, Ceylon Tamils were migrating to work as clerks for British officers in British Malaya. The progress and abundant opportunities in British Malaya, attracted more professionals - doctors, lawyers, journalists, teachers - to migrate to the Straits Settlements, Federated Malay States and the Unfederated Malay States.

North Indians from established business communities like the Parsis, Gujaratis, and Sindhis migrated to Singapore and Penang, taking advantage of the trade openings there.

Eventually, Indians became a common sight in government offices, working for British officials alongside a small, albeit growing number of professionals setting up their own businesses. This became particularly common and grew during the post independence era in Malaysia. There was a time in the 1970s when Indians made up over 50% of the workers in medical services.

1970s to present day - Indians in Malaysian politics and local industries

Malaysia began sourcing for IT specialists and economists from India, as it progressed towards becoming an industrialised economy in the 70s.

Three decades later, as the country expanded its technology industry and began hosting many multinational corporations, more Indian professionals arrived in the the country - especially after Malaysia signed the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on manpower recruitment with India in March 2005.

Today, most Malaysian Indians are descendents of Indian nationals that came in as workers and traders during the colonial era.

Alongside the Chinese and other minor groups that migrated to Malaysia in the past, Indians have penetrated various industries, carving a name for themselves in the country

From left: Ananda Krishnan, Ambiga Sreenevasan, Tony Fernandes.

Image via Marco Polis/Jom Magazine/WartabuanaBusinessman, philanthropist, and one of the richest man in the world Ananda Krishnan, AirAsia extraordinaire, entrepreneur Tony Fernandes, and former president of the Malaysian Bar Council, activist Ambiga Sreenevasan, are just some of the Malaysian Indians that have found success and recognition locally.

In terms of politics, Dato' Seri Samy Vellu Sangalimuthu, the longest-serving President of the Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC), held various ministerial posts in the Cabinet of Malaysia, including two long stints as the Malaysian Minister of Works, while Datuk Seri Dr S. Subramaniam is the current Malaysian Minister of Health.

Despite the successes of these individuals and others like them, the Indian community in Malaysia is still lagging in terms of socio-economic development. MIC's social welfare arm, Yayasan Pemulihan Social (YPS), said that about 40% of Malaysian Indians are still at the bottom of the income ladder in 2015.

Malaysian Indians have also been widely associated with crime, especially gang-related offences. A documentary by Al Jazeera in 2014, revealed that almost 70% of gang members and felons in Malaysia are Indians. These criminals are linked to a number of offences including drug and prostitution rings, armed robberies, and contract killings, to name a few.

To curb these criminal activities, organisations like the Educational, Welfare & Research Foundation Malaysia (EWRF) are working towards ensuring that Indians do not stray into such offenses with the power of education.