Amidst Starvation And COVID-19: Why The Rohingya Are Still Risking Dangerous Sea Crossings

The Rohingya — rendered stateless — have been victims of crimes that constitute genocide. The response to the COVID-19 pandemic should not be an excuse to block them from landing safely and seeking asylum.

Editor's Note: This story is the personal opinion of the writer/organisation. You too can submit a story as a SAYS reader by emailing us at [email protected].

Shocking footage of Rohingya women, men, and children stumbling off rickety boats after dangerous sea voyages is being broadcast around the world

A boat carrying hundreds of Rohingya people landed in Bangladesh two weeks ago after an unsuccessful attempt to make it to Malaysia. They were the "lucky" ones — dozens of their companions reportedly died of starvation at sea over the months-long journey.

A boat thought to be carrying Rohingya migrants is detained off Malaysia earlier in April.

Image via The GuardianSeveral boats are currently adrift with nowhere to land, as countries ignore international obligations to allow safe disembarkation under the cover of COVID-19 restrictions.

The policies risk repeating the same mistakes from 2015 when the break-up of trafficking networks left thousands starving and stranded in Southeast Asian waters.

Here, Amnesty International explains why Rohingya are still risking everything to flee crowded refugee camps in Bangladesh; how countries in the region can help; and why these people shouldn't be sent back to Myanmar.

Who are the Rohingya people?

The Rohingya are a predominantly Muslim ethnic minority in Myanmar. Until recently, more than a million of them lived mostly in Rakhine State, in the west of the country near the border with Bangladesh.

Virtually all of them have had their citizenship revoked and have no reasonable claim to citizenship in any other country. Myanmar insists that there is no such group in the country, instead claiming that they are "illegal immigrants" from Bangladesh. Its refusal to recognise them as citizens renders the majority of them stateless.

Their lack of citizenship has had a number of deeply negative impacts on their lives and has allowed the authorities in Myanmar to severely restrict their freedom of movement, effectively segregating them from the rest of society. As a result, they struggle to access healthcare, schools, and jobs.

This systematic discrimination amounts to apartheid, a crime against humanity under international law.

How have so many Rohingya ended up in Bangladesh as refugees?

Since August 2017, more than 740,000 Rohingya have fled their homes in Myanmar's northern Rakhine State after the military unleashed a brutal campaign of violence against them.

During this campaign, launched in response to coordinated attacks on security posts by the armed group the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) on 25 August 2017, security forces killed thousands of Rohingya people, raped women and girls, hauled men and boys off to detention sites where they were tortured, and burned hundreds of homes and villages to the ground in what were clearly crimes against humanity.

A United Nations (UN) report has concluded these crimes may also constitute genocide.

In the years after the campaign, Rohingya have continued to flee across the border in smaller numbers, escaping persecution and increased armed conflict in Rakhine state. In October 2018 a representative of a UN fact-finding mission said "it is an ongoing genocide" in Myanmar.

While the crisis in Rakhine State since August 2017 is unprecedented in the scale of displacement, this is not the first time the Rohingya have been subject to violent expulsion from their homes, villages, and country at the hands of the Myanmar state. In the late 1970s and again in the early 1990s, hundreds of thousands of people were forced to flee to Bangladesh after major military crackdowns, which were accompanied by wide-ranging human rights violations.

More recently, in what many saw as a prelude to the 2017 violence, almost 90,000 Rohingya were forced to flee to Bangladesh after Myanmar security forces responded to attacks on police posts by ARSA in 2016. The campaign of violence targeted the community as a whole. At the time, Amnesty International concluded that these actions may have amounted to crimes against humanity.

Today, estimates place the number of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh at nearly 1 million.

Why are Rohingya still fleeing by boat?

Living in apartheid conditions in Myanmar and constrained by a lack of livelihood opportunities in the refugee camps in Bangladesh, the Rohingya have made attempts to reach Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and other countries. Lacking visas, travel documents, and subject to strict restrictions on movement that make overland connections nearly impossible, boats are often their best and only option.

While the Bangladeshi government has generously hosted these refugees, it has not given the vast majority refugee status — leaving them without legal status on either side of the border. Bangladesh is not a state party to the 1951 UN Convention related to the Status of Refugees or its 1967 Protocol.

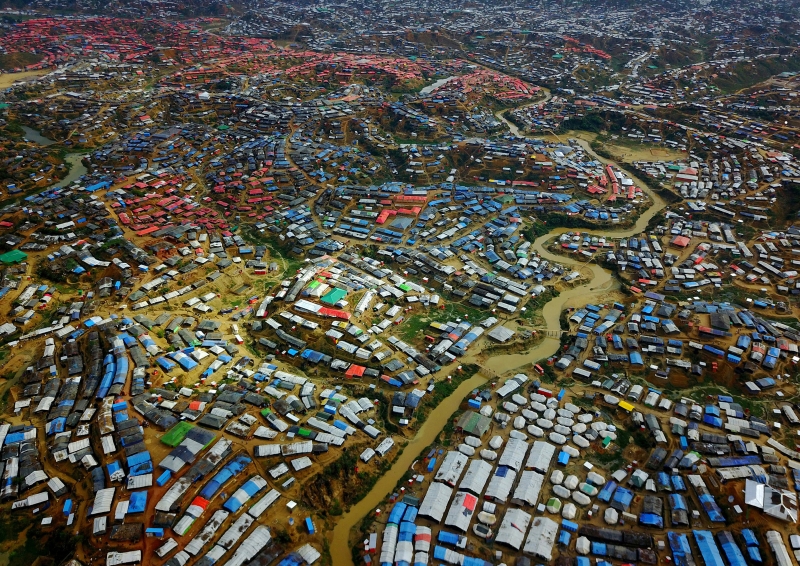

In Bangladesh, Rohingya are squeezed into threadbare shelters, mostly made of flimsy tarpaulin and bamboo. During the upcoming monsoon season due in June, many homes could be damaged, as has been the situation in previous years. Cox's Bazar, where most of the Rohingya refugees are located, is prone to both landslides and flash floods. A cyclone during this period would make the situation even worse.

The camps are extremely congested with a density of 40,000 people per square kilometre. The area where most of the Rohingya refugees have taken shelter is large enough to count as Bangladesh's fourth-largest city, with nearly a million people, including the local host community.

Bangladesh authorities have imposed sweeping Internet shutdowns on the refugee camps, leaving the community increasingly isolated and unable to access crucial information on how to protect themselves in the pandemic, even as COVID-19 threatens to kill many people in the cramped quarters of the camps.

The view of Kutupalong refugee camp in Cox's Bazar where Rohingya refugees have sought shelter.

Image via Food Security ClusterWhy can't Rohingya people return to Myanmar?

Rohingya people are at risk of serious human rights violations in Myanmar and are prima facie refugees. International law — in particular the principle of non-refoulement — forbids states from returning people to a place where their lives or freedoms would be at serious risk.

Indeed, the UN has repeatedly stated that conditions in Myanmar are not conducive to returns. Conditions in Myanmar have deteriorated further in the context of ongoing fighting between the Arakan Army – a separate armed group calling for more autonomy for ethnic Rakhine Buddhists – and the Myanmar military, which escalated in January 2019.

The Rohingya have an inalienable human right to return to and reside in Myanmar — it is their home, and if they choose to, they must be allowed to return. But governments must not organise returns unless they are safe, voluntary, sustainable, and dignified.

As part of this, the entrenched system of discrimination and segregation that made the Rohingya flee in the first place has to be dismantled. Safe and dignified returns mean guaranteeing that once back, they can enjoy equal rights and citizenship and that widespread and systematic human rights violations — including crimes under international law — will stop.

Safe and dignified returns also require those responsible for the horrific abuses against the Rohingya to be held to account. As it stands, almost all perpetrators remain at large and continue to evade justice, while maintaining positions of power that enable them to perpetrate more violations. The Rohingya cannot be left living in fear of a fresh wave of violence that will, if they survive, drive them across the border yet again.

In January 2020, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ordered Myanmar to take "provisional measures" to prevent genocidal acts against the Rohingya community after The Gambia filed a case accusing Myanmar of breaching its obligations under the 1948 Genocide Convention.

However, the Court has no jurisdiction to try individuals accused of genocide against the Rohingya and war crimes against minorities in Rakhine, Kachin, and northern Shan states. Therefore, the UN Security Council must refer the situation in Myanmar to the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Arakan Army recruits train at the group's headquarters in Laiza, Kachin State, near the Chinese border.

Image via Hkun Lat/FrontierIs it possible to take in boats without increasing the risk of COVID-19 outbreak?

Many countries are able to contain COVID-19 by testing people on arrival and putting people in quarantine for a limited time before allowing them to enter the country.

Mandatory quarantines at borders are in place for new arrivals in many states. Explicit exemptions from entry bans or border closures for asylum seekers are provided for by over 20 countries in Europe for example. Many states have also issued documentation to refugees and asylum seekers, to ensure legal stay and access to services.

On 5 April 2020, the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency intercepted a boat carrying over 200 Rohingya people, who were brought to safety and placed in COVID-19 quarantine. There has been no reported outbreak of COVID-19, amongst those that were rescued showing that successful disembarkation is easily possible.

International organisations including the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), have said that they stand ready to help Malaysia deal with any further boats requiring rescue and to ensure that they do not pose a health risk. The Malaysian government should accept their offer of help, and act to save lives.

Changes in immigration policy should be introduced alongside accepting aid from international organisations. Migrants have a right to liberty and should not be placed in immigration detention centres that have been well-documented for being unsanitary and overcrowded.

These conditions would accelerate the spread of COVID-19 among migrants and refugees. To prevent this, the government should consider alternatives to detention. Detention solely for migration-related reasons is not justifiable, especially during a global pandemic.

What should happen now?

South and Southeast Asian governments must immediately launch search and rescue operations for Rohingya stranded at sea, bringing food and medicine, and allowing safe disembarkation.

Authorities must not forcibly push boats back.

The response to the COVID-19 pandemic should not be an excuse to block Rohingya from landing safely and seeking asylum.

Authorities should ensure UNHCR has full and unimpeded access to those who arrive by boat. Moreover, Rohingya should only be held in detention for the minimum time required for purposes of identity verification and/or quarantine.

The governments of Bangladesh and Myanmar must also uphold their stated commitment that Rohingya refugees will only return safely, voluntarily, and with dignity. Both governments must ensure that refugees in Bangladesh are able to make free and informed choices about return, based on access to full and impartial information about conditions in Rakhine State and the support to remain in Bangladesh if they choose to do so.

Both governments must also ensure that Rohingya are consulted and included in all decisions affecting their futures. At the moment, Rohingya refugees do not have a seat at the table, and decisions about their future are being made without their knowledge and therefore obviously without their consent.

They should also allow the free flow of information in both the crowded camps in Bangladesh and in parts of Myanmar's northern Rakhine and southern Chin States — where the Internet is also currently blocked — so that Rohingyas are fully aware of measures to respond to the pandemic and how to protect themselves and their family members.

Aside from Internet access, measures specifically aimed at protecting older refugees need to be taken, as many do not have access to smartphones. In addition, there is an urgent need for access to clean water, soap, and help with social distancing measures for all refugees to fully ensure the right to health during the pandemic.

The international community must also do much more to support Bangladesh and share the responsibility and financial burden of hosting almost a million refugees at a time its economy is already under strain from the pandemic-related global slowdown. Finally, Rohingya refugees are entitled to continue to seek asylum and states must keep borders open to refugees who continue to flee now or will do so in the future.

Rohingya refugees gather after being rescued in Teknaf near Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh in April.

Image via Suzauddin Rubel/AP PhotoWhy should governments welcome refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants?

Rohingya people have been forced to flee their homes. But instead of showing leadership, politicians are dehumanising refugees and playing on people's fears in a time of crisis. Every single day that goes by, their indecision and failure to prioritise human life continues to cause immense human suffering.

Host countries of refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants benefit from the contributions of individuals grateful to have been provided sanctuary and eager to start new lives.

Refugees can positively contribute to the economy if they are given permission to work

Pilot projects that allowed Rohingya UNHCR cardholders to work should be extended. Welcoming people from other countries can also strengthen host countries by making them more diverse and flexible in our fast-changing world.

Malaysia, like other prosperous nations, has relied on foreign labour since independence. Foreign workers in Malaysia comprise 30-40% of our workforce and are an essential backbone to our society.

They work as construction workers, security guards, cleaners, waiters, and cooks, and in our supermarkets, retail shops, and healthcare services. This time of national emergency has shown how indebted we are to migrant workers more than ever.

We should not forget that some of the most inspiring and influential people in the arts, science, politics, and technology have been refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants. They were allowed to rebuild their lives in a new country and thrived.

All countries can help protect refugees through a solution called resettlement, and other safe and legal routes. Opening up these opportunities for refugees will allow them to travel to new host countries in a safe, organised way.

Malaysia should lead by example, and work with other countries to share the burden.

To avoid a situation like the 2015 Andaman sea crisis when an untold number of Rohingya people were not rescued and hundreds lost their lives, there is an urgent humanitarian need to rescue boats that are still adrift.

The COVID-19 pandemic cannot justify refusal for Rohingya people to disembark. For every day that these men, women, and children remain stranded on boats, their lives are in danger.

Some of the over 1,000 foreigners who were detained around the KL Wholesale Market on 12 May.

Image via Jabatan Imigresen MalaysiaThe Rohingya crisis is a shared responsibility among all countries

Refugees and migrants are humans with their own families they love and have dreams and ambitions of their own. It is of paramount importance that we extend humanity and compassion to refugees, share correct information, and stop stereotyping them.

Malaysia can no longer remain silent about the suffering right outside our borders.