3 Key Points That Helped Indira Gandhi Win Her Case Against Unilateral Conversion

The case ruling is now hailed as a landmark decision by the Federal Court.

On 29 January, the Federal Court unanimously nullified the conversion of M. Indira Ghandi's children to Islam

A five-man panel, chaired by Court of Appeal president Tan Sri Zulkefli Ahmad Makinudin, unanimously ruled in Indira's favour after allowing her final appeal to challenge the validity of her children's conversion to Islam.

Federal Court judge Tan Sri Zainun Ali read out a summary of the 99-page judgement on the case, and there are three main points in it that might set a precedent for future similar cases.

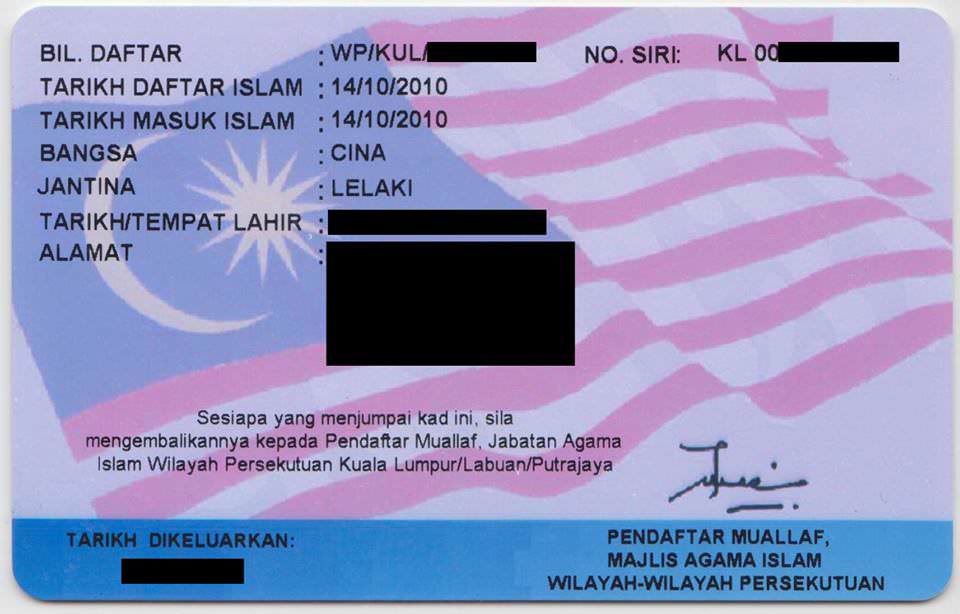

1. The Registrar of Muallafs had no power to issue conversion certificates when the requirements to register someone's conversion to Islam were not fulfilled

In the press summary of the judgement, the Federal Court ruled that there were strong evidence that Indira's children did not fulfil the requirements listed in the Perak Enactment to be converted to Islam.

Indira's children had to utter two clauses of the affirmation of faith, and be present in front of the Registrar of Muallafs in order for the conversion to be valid. Section 96 of the Enactment states the requirements that need to be complied with for a valid conversion of a person to Islam.

The Federal Court decided that the Registrar of Muallafs had no power to issue the conversion certificates as Indira's children were not present before the Registrar, and neither did they utter the two clauses of affirmation of faith.

2. Shariah courts cannot exercise the judicial powers of civil courts, such as judicial reviews

The summary contains a section dedicated to judicial limits of Shariah courts. It also emphasises on the powers of civil courts, especially the jurisdiction to review lawfulness of executive action.

On top of that, Article 121 (1A) of the Federal Constitution gives civil courts the jurisdiction in interpreting legislation, even in relation to the administration of Muslim law. No constitutional amendments can be made to remove this power from civil courts.

The Shariah court is also not allowed to determine to validity of someone's conversion to Islam. This is already under the jurisdiction of civil courts, as it concerns the legality and constitutionality of the actions taken by the Registrar of Muallafs.

3. Unilateral conversion contravenes the Guardianship of Infants Act 1961 (GIA) and the Federal Constitution

The judges first clarified that provisions in the Federal Constitution cannot be interpreted literally, particularly in respect of Article 12(4). The real reason why the term "parent" was used in the Constitution was to provide for a situation where a single parent is involved.

The judges also concluded that the literal understanding of Article 12(4) would lead to consequences which wasn't intended in the first place, as it was just a case of being lost in translation. Furthermore, equality of parental right regarding an infant was already written in the GIA.

The judges were most concerned with the welfare of the children involved, and how the conversion to another religion would impose "new and different set of personal laws" on the children. Conversion of the husband to Islam does not take the children away from the protection of the GIA.

Although the ruling was proclaimed as a win for civil law in Malaysia, the Malaysian Muslim Lawyers Association now wants Shariah court to be put on par with civil courts

President of the association Datuk Zainul Rijal Abu Bakar also raised his concerns that the ruling would be used by certain parties to reintroduce Section 88A of the Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) Act 1976, which was previously struck down for being unconstitutional.

The amendment would have banned unilateral child conversion to Islam.

The Malaysian Association of Muslim Scholars (PUM) has also urged the police to stop pursuing Indira's ex-husband, warning that religious sectarian violence may erupt if the police proceed with the hunt.