13 Heartbreaking Photos To Make Sense Of The Crisis Surrounding The Stateless Rohingyas

Disowned and denied, they have nowhere to go.

On 14 May, a fishing boat carrying several hundred desperate migrants from Myanmar was spotted adrift in the Andaman Sea between Malaysia and Thailand, according to the NYT. They are a part of an exodus in which thousands of people have taken to the sea in recent weeks with no country willing to take them in.

Rohingya migrants bring back food supplies dropped by a Thai army helicopter after jumping to collect them at sea on 14 May 2015.

Image via Huffington PostAccording to reports, Malaysia has turned away two boats containing 800 migrants, and Indonesia and Thailand have likewise reportedly turned away boats in recent days. While the Human Rights Watch says there are as many as 8,000 people currently stranded at sea, several media reports put the figure at 6,000.

Rohingya migrants swim to collect food supplies dropped by a Thai army helicopter after they jumped off a boat drifting in Thai waters off the southern island of Koh Lipe, 14 May 2015.

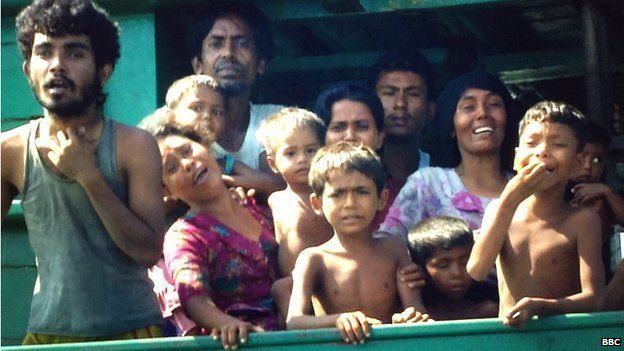

Image via Huffington PostIn this photo dated 14 May 2015, Rohingya migrant women cry as they sit on a boat drifting in Thai waters. The boat was crammed with scores of Rohingya migrants, including many young children.

According to the UN's refugee agency, many people on the boats are running out of food and water. Meanwhile a BBC report on Thursday said that 10 people on one boat have died so far...

...and in desperation, some of them are resorting to drinking urine!

Rohingya refugees are pictured on a boat off the southern Thai island of Koh Lipe in the Andaman Sea on 14 May 2015.

Image via Huffington PostPhil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch's Asia division told the BBC: "They're [Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia] playing a game of marine ping-pong not wanting to take in the Rohingyas.

He said it was necessary for the three countries to work together in rescuing them before they decide who is going to take responsibility for them. "This is an urgent humanitarian crisis and the Thais and others seem to be taking a gentle stroll."

The dead bodies were thrown overboard. While the fate of the migrants is not clear as all the countries in the region - Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia – have said they will not allow them to land.

“What we have now is a game of maritime Ping-Pong,” said Joe Lowry, a spokesman for the International Organization for Migration in Bangkok. “It’s maritime Ping-Pong with human life. What’s the endgame? I don’t want to be too overdramatic, but if these people aren’t treated and brought to shore soon, we are going to have a boat full of corpses.”

In this photo dated 14 May 2015, a Rohingya woman cries as she stands on a boat drifting in Thai waters off the southern island of Koh Lipe. Only a few boats have been able to reach safe shore.

A sick rescued migrant is assisted by other migrants on their arrival at the new confinement area in the fishing town of Kuala Langsa in Aceh province. Indonesian fishermen and marine police rescued nearly 800 migrants from a sinking vessel on 15 May 2015.

The migrants, mostly thought to be people from Myanmar and Bangladesh from the Rohingya ethnic group, were initially prevented from reaching the shore pending a consultation with the Foreign Ministry, military spokesman Fuad Basya said. Despite the risks, the Rohingya continue to leave Myanmar in large numbers, fleeing anti-Muslim violence and discrimination in the predominantly Buddhist country.

Interviews with passengers onboard a boat that washed ashore on the northern tip of Sumatra Island, Indonesia, on Sunday, 10 May 2015, provided a glimpse of the brutal conditions they faced at sea and the desperation that drove them to make the risky voyage

Rohingya migrants sit on a boat drifting in Thai waters off the southern island of Koh Lipe, 14 May 2015.

Image via Christophe Archambault/AFP/Getty ImagesPassengers told of waiting on the boat for months before it sailed because the smugglers wanted to pack it as full as possible with paying passengers.

Most were forced to remain in the hold, squatting no more than an inch from the person in front of them. Every other day, they were fed bits of rice and noodles and small amounts of water. A hole in the floor, opening directly into the ocean, served as a toilet.

The passengers prayed or talked quietly, their whispers broken by the occasional sound of others vomiting from seasickness. “There was no singing, only crying,” said Muhammed Kashim, a 44-year-old Bangladeshi.

Mahammed Hashim, 25, a Rohingya from the Kyauktaw District in Rakhine State, said the risks of traveling in a rickety wooden ship with little food or water were less than those of remaining in Myanmar.

“We assumed that danger would come, but there was no other way,” he said. “We were living in a country that is more dangerous than the sea.”

Rohingya migrants on a boat drifting in Thai waters off the southern island of Koh Lipe; and a Rohingya refugee with her child on the same boat