What You Should Know About ISIS' Latest Beheading Of An Ex-Soldier Turned Humanitarian

His name was Abdul-Rahman Kassig, born Peter Kassig. He was captured in 2013 while helping provide medical aid to Syrians.

On 16 November 2014, a YouTube video posted by ISIS showed Jihadi John, a nickname given to an ISIS fighter known for his role as the apparent executioner in several beheading incidents in 2014, standing over a severed human head, now confirmed to be of 26-year-old Peter Kassig, also know as Abdul-Rahman Kassig

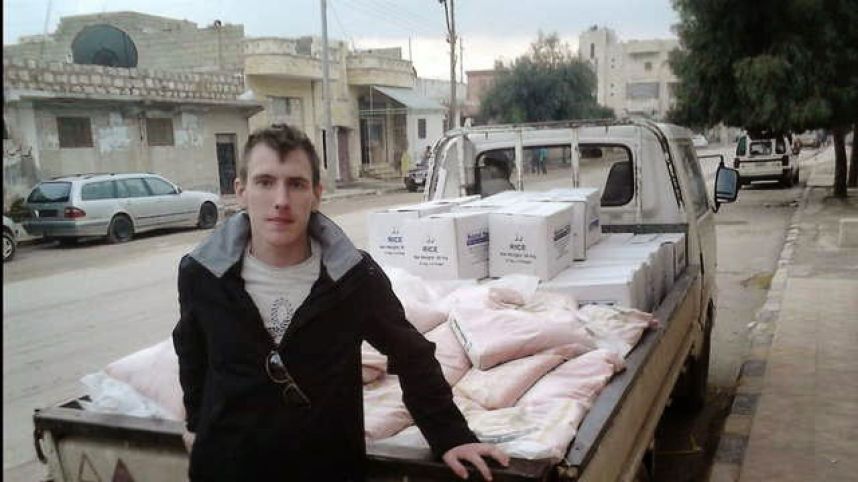

Peter Kassig in front of a truck somewhere along the Syrian border between late 2012 and autumn 2013 as Special Emergency Response and Assistance (SERA) was delivering supplies to refugees

Image via dailymail.co.ukThe video was released by al-Furqan Media, which is controlled by Isis. It showed a man who looked and sounded like a British-accented fighter seen in other such videos, standing over what appeared to be Kassig’s severed head.

Kassig, a former army ranger who served in Iraq before returning to the Middle East and founding a humanitarian group, was captured in October 2013.

Previously on 3 October 2014, at the end of a video showing beheading of Alan henning, a British aid worker, the ISIS had threatened the life of Kassig, a former American Army Ranger turned air worker, blaming Obama and his renewed military action in Syria and Iraq for his and other hostages' deaths

Kassig is the fifth western hostage to be killed by ISIS. Two American journalists, James Foley and Steven Sotloff, and the British aid workers David Haines and Alan Henning, were the others to be beheaded before Kassig.

In response to Kassig's beheading, US President Obama, in a statement that referred to the name the Indiana native adopted (Peter Kassig was born and raised in Indianapolis, Indiana), after converting to Islam while in captivity, said:

“We offer our prayers and condolences to the parents and family of Abdul-Rahman Kassig, also known to us as Peter. We cannot begin to imagine their anguish at this painful time.”

Obama was speaking to reporters aboard Air Force One on his return from the G20 summit in Brisbane, Australia. He praised Kassig as a humanitarian killed “in an act of pure evil” by Isis. The president said the group “revels in the slaughter of innocents, including Muslims, and is bent only on sowing death and destruction”.

“These were the selfless acts of an individual who cared deeply about the plight of the Syrian people,” Obama said. In his statement, Obama said: “[Isis’s] actions represent no faith, least of all the Muslim faith which Abdul-Rahman adopted as his own.”

On 17 November, the parents of Kassig said their "hearts are battered" and they need time to "mourn, cry – and yes – forgive"

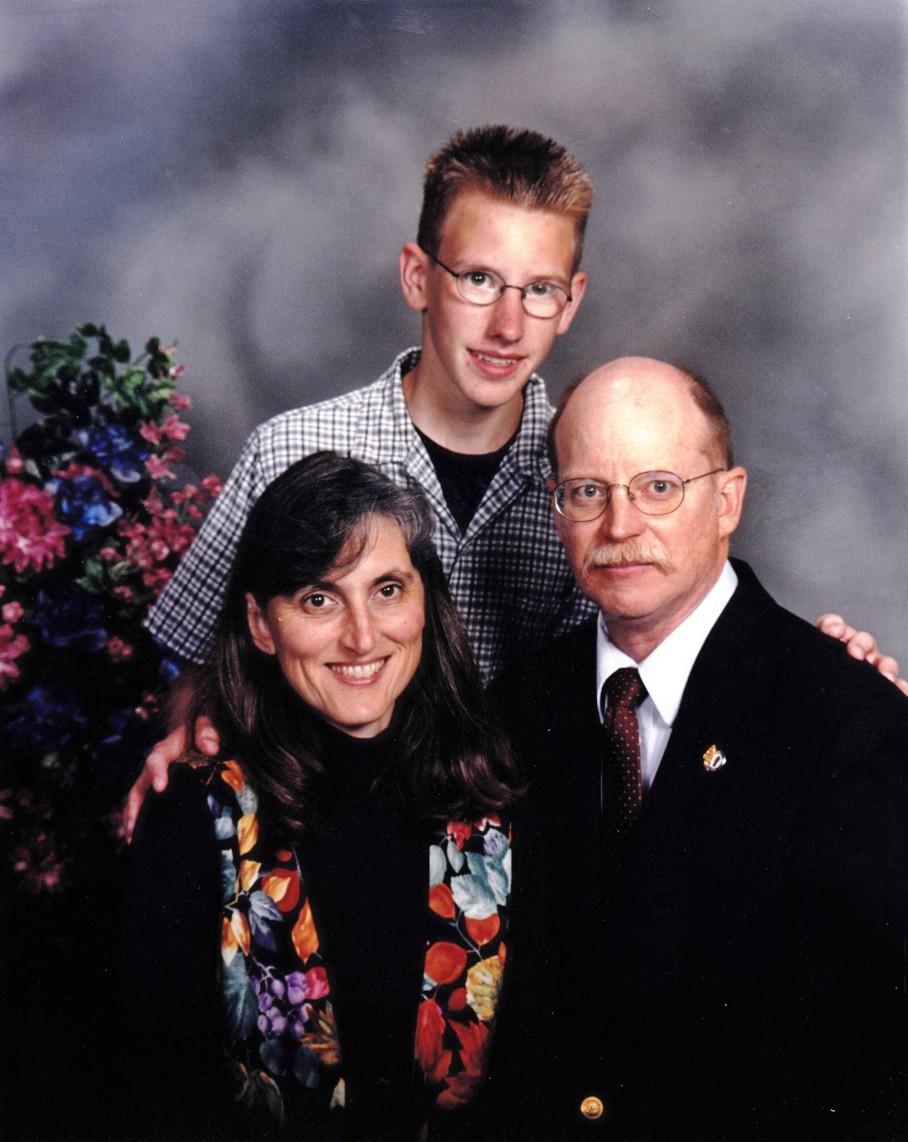

Ed and Paula Kassig listen to a speaker during a prayer vigil for their son Abdul-Rahman Kassig, known as Peter before he converted to Islam, on the campus of Butler University in Indianapolis on 8 October 2014

Image via nydailynews.com"Our hearts are battered, but they will mend. The world is broken, but it will be healed in the end. And good will prevail as the One God of many names will prevail," his mother, Paula Kassig, said at a news conference at Epworth United Methodist Church in Indianapolis.

go.com"Please pray for Abdul-Rahman, or Pete if that's how you know him, at sunset this evening," his father, Ed Kassig, said. "Pray also for all people in Syria, in Iraq, and around the world that are held against their will. And lastly, please allow our small family the time and privacy to mourn, cry -- and yes, forgive -- and begin to heal," he said.

cnn.comBoth his parents also asked people not to focus on his murder and, instead, to keep "his legacy alive"

“We prefer our son is written about and remembered for his important work and the love he shared with friends and family, not in the manner the hostage takers would use to manipulate Americans and further their cause,” they said in a statement reported by the Indianapolis Star.

washingtonpost.comKassig was an only child who grew up in Broad Ripple, Ind., a small town outside Indianapolis. His father taught science, and his mother worked as a nurse. He ran track and played guitar. And after he graduated from high school, he reportedly joined the U.S. Army Rangers and served four months in Iraq. Then he was honorably discharged for medical reasons. He got married and divorced. He took some college courses. He trained as an emergency medical technician.

washingtonpost.comIn 2012, Kassig told his parents he finally found his calling. He wanted to help others. During spring break in 2012, he flew to Lebanon while studying political science at Butler University.

“Here, in this land, I have found my calling,” he wrote in an e-mail to friends and teachers, the Indianapolis Star reported. “Yesterday my life was laid out on a table in front of me. With only hours left before my scheduled flight back to the United States, I watched people dying right in front of me. I had seen it before and I had walked away before…. I have run until I could not run any more.”

washingtonpost.comHe stayed, and bandaged wounds, cared for people in clinics, and, just generally, helped. He was drawn across the Syrian border into a zone of both war and jihadi kidnapping. Joshua Hersh, who encountered Kassig when he was working there, wrote that he “didn’t try to convince me that going back was safe, or even wise. But his commitment to the relief project he had embarked on was untempered, and it was clear to me that he would soon go back.”

Those who knew him said it was his drive that set him apart

“While friends drank beer at bars on Gemmayze Street, Kassig grabbed camping gear and set out for the mountains,” journalist Joshua Hersh wrote in the New Yorker. “He visited the Palestinian refugee camps that dot the landscape around Beirut, thinking about ways to bring solar power and other utilities into those neglected communities. Later, as the war in Syria encroached on Lebanon’s borders, sending desperate and wounded civilians into rural communities in the north, Kassig traveled to Tripoli to volunteer his services at a clinic, suturing wounds and comforting the dying.”

washingtonpost.com