The US Secretly Made Its Own 'Twitter' To Incite Unrest Among The Cubans

The program evaded restrictions by creating a texting service that can be used to organize political protests.

The U.S. government created its own version of Twitter based on SMS messaging to help undermine the Cuban government and create unrest, the AP reports

Joe McSpedon, a official of the U.S. Agency for International Development, leaves his house on Monday, March 31, 2014, in Washington. McSpedon worked on a USAID project that funded and helped create a "Cuban Twitter," a communications network designed to undermine the communist government in Cuba, built with secret shell companies and financed through foreign banks

Image via ap.orgIn July 2010, Joe McSpedon, a U.S. government official, flew to Barcelona to put the final touches on a secret plan to build a social media project aimed at undermining Cuba's communist government. McSpedon and his team of high-tech contractors had come in from Costa Rica and Nicaragua, Washington and Denver. Their mission: to launch a messaging network that could reach hundreds of thousands of Cubans.

To hide the network from the Cuban government, they would set up a byzantine system of front companies using a Cayman Islands bank account, and recruit executives who would not be told of the company's ties to the U.S. government. McSpedon didn't work for the CIA. This was a program paid for and run by the U.S. Agency for International Development, best known for overseeing billions of dollars in U.S. humanitarian aid.

Named 'ZunZuneo', it was designed to be a 'Cuban Twitter' that will work without the web and build an audience using safe content initially and later the plan was to introduce contents that were critical in nature

Documents show the U.S. government planned to build a subscriber base through "non-controversial content": news messages on soccer, music and hurricane updates.

Later when the network reached a critical mass of subscribers, perhaps hundreds of thousands, operators would introduce political content aimed at inspiring Cubans to organize "smart mobs" — mass gatherings called at a moment's notice that might trigger a Cuban Spring, or, as one USAID document put it, "renegotiate the balance of power between the state and society."

ZunZuneo had around 40,000 Cubans on its network at its peak popularity, and at no time did the network make anyone aware that it was involved with the U.S. government or its contractors

In this March 11, 2014 photo, a woman uses her cellphone as she sits on the Malecon in Havana, Cuba. The U.S. Agency for International Development masterminded the creation of a "Cuban Twitter," a communications network designed to undermine the communist government in Cuba, built with secret shell companies and financed through foreign banks

Image via ap.orgAt its peak, the project drew in more than 40,000 Cubans to share news and exchange opinions. But its subscribers were never aware it was created by the U.S. government, or that American contractors were gathering their private data in the hope that it might be used for political purposes.

"There will be absolutely no mention of United States government involvement," according to a 2010 memo from Mobile Accord, one of the project's contractors. "This is absolutely crucial for the long-term success of the service and to ensure the success of the Mission."

bellinghamherald.comThe program's legality is unclear: U.S. law requires that any covert action by a federal agency must have a presidential authorization and that Congress should be notified

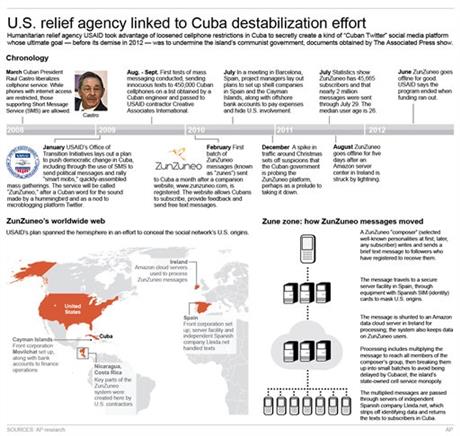

Graphic shows chronology of events surrounding ZunZuneo message service, map of distribution of ZunZuneo resources and flow chart of text messages

Image via ap.orgThe Obama administration on Thursday said the program was not covert and that it served an important purpose by helping information flow more freely to Cubans. Parts of the program "were done discreetly," Rajiv Shah, USAID's top official, said on MSNBC, in order to protect the people involved.

The administration also initially said Thursday that it had disclosed the program to Congress — White House spokesman Jay Carney said it had been "debated in Congress" — but hours later shifted that to say it had offered to discuss funding for the program with several congressional committees. "We also offered to brief our appropriators and our authorizers," State Department spokeswoman Marie Harf said.

Two senior Democratic lawmakers said they knew nothing about the effort, and the Republican chairman of a House oversight subcommittee said his panel plans to look into the initiative next week. "If you're going to do a covert operation like this for a regime change, assuming it ever makes any sense, it's not something that should be done through USAID," said Sen. Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., chairman of the Senate Appropriations subcommittee that oversees USAID's budget.

The government agency responsible for creating the “Cuban Twitter” was actually the U.S. Agency for International Development, and it isn’t denying its involvement, or the efforts to keep its involvement secret

The USAID is designed to “help people exercise their fundamental rights and freedoms, and give them access to tools to improve their lives and connect with the outside world,” a spokesman for the agency told the AP, and claims that hiding its involvement was just designed to protect the citizenry involved.

Eventually, the program grew beyond what the government contractors felt they could control, and they realized they needed to exit their involvement to in order to conceal their role

At one point, the USAID even went to Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey to seek funding for ZunZuneo, which was part of a plan for it to go independent and become a legitimate business, with the proviso that new management keep its original ambitions for inspiring political change.

After those plans failed, ZunZuneo was shuttered around mid-2012, which the USAID says was the result of the program simply running out of money

Toward the middle of 2012, Cuban users began to complain that the service worked only sporadically. Then not at all. ZunZuneo vanished as mysteriously as it appeared. By June 2012, users who had access to Facebook and Twitter were wondering what had happened.

Users were apparently mystified and disappointed when it went dark, given how popular it had become.

In the end, "Cuban Twitter" is a strange story of a start-up along with a sign of a flawed strategy

It’s a strange story about how a government agency sought to foment the seeds of revolution using the playbook of Twitter, which has become a key tool for voicing political dissent and organizing in politically charged countries around the world, including Egypt, the Ukraine and Turkey.

Perhaps the oddest part is that it ran into a typical startup problem, resulting in its ultimate end: how to scale effectively.

washingtonpost.com