DBKL Explains Market Ban On Foreigners After Human Rights Groups Express Concern

The ban, which restricts foreigners and refugees from entering the wholesale market, has sparked mixed reactions from several individuals and organisations.

On Tuesday, 23 June, Kuala Lumpur City Hall (DBKL) released a statement clarifying the market ban on foreigners after the issuance drew mixed reactions from various individuals and organisations last Friday

The ban, which restricts foreigners and refugees from entering Kuala Lumpur Wholesale Market (PBKL), was enforced in order to prevent the illegal resale of wholesale items elsewhere, DBKL said.

"United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) card holders are also not allowed to buy wholesale for fear that they would abuse this opportunity by illegally reselling items somewhere else, either to anyone interested or to the Rohingya and Myanmar communities," read the statement.

Because the market is only open for wholesale and not retail, the press release suggested that foreigners buy their daily necessities at nearby markets, including Selayang Daily Market.

DBKL added that this ban is part of their efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19

Located in Selayang, the market was temporarily closed for four days in April after it was identified as a COVID-19 cluster where a 36-year-old Myanmar man had died, as reported by Malay Mail.

Due to this, DBKL explained that foreigners' movements have to be monitored. Their statement said, "This [the ban] is to ensure that PBKL, a vital part of business in Kuala Lumpur, can continue to function smoothly without closure."

With foreigners forming approximately 90% of market workers, DBKL officials noted that, "Such control over foreigners entering PBKL is to change public perception that the market is controlled by them."

However, human rights groups in Malaysia saw the ban differently

In a joint statement, Rohingya Women Development Network (RWDN) and Fortify Rights, expressed their concern about recent actions taken against refugees and migrants in Malaysia.

"Without the rights to work in Malaysia, refugee livelihoods largely depend on the informal economy where they work as day labourers in hospitality, construction, and factories, often earning less than RM1,000 per month," read the statement.

They continued, "Further complicating the situation for refugees, DBKL banned refugees from entering the wholesale market in Selayang - a large outdoor market relied on by residents in the area to secure fresh, affordable food."

A YouTube video created by Fortify Rights noted that an estimated 15,000 Rohingya refugees reside in Selayang, many of whom were employed at the market.

Interviewing several refugees about their experiences living in Malaysia, RWDN and Fortify Rights found that food insecurity was a major worry for these communities

A 25-year-old Rohingya refugee woman was quoted as saying, "If the food we have runs out, God knows what will happen to us."

Another woman mirrored that sentiment exclaiming, "We refugees are going to die from hunger, not because of COVID-19, but because of a lack of food. And [if we] can't pay the rent, the landlord will kick everyone out."

Refugees are ineligible for the wage subsidy programme provided by the Malaysian government to support workers with monthly incomes of RM4,000 or less under the 'Prihatin Rakyat Economic Stimulus Package'.

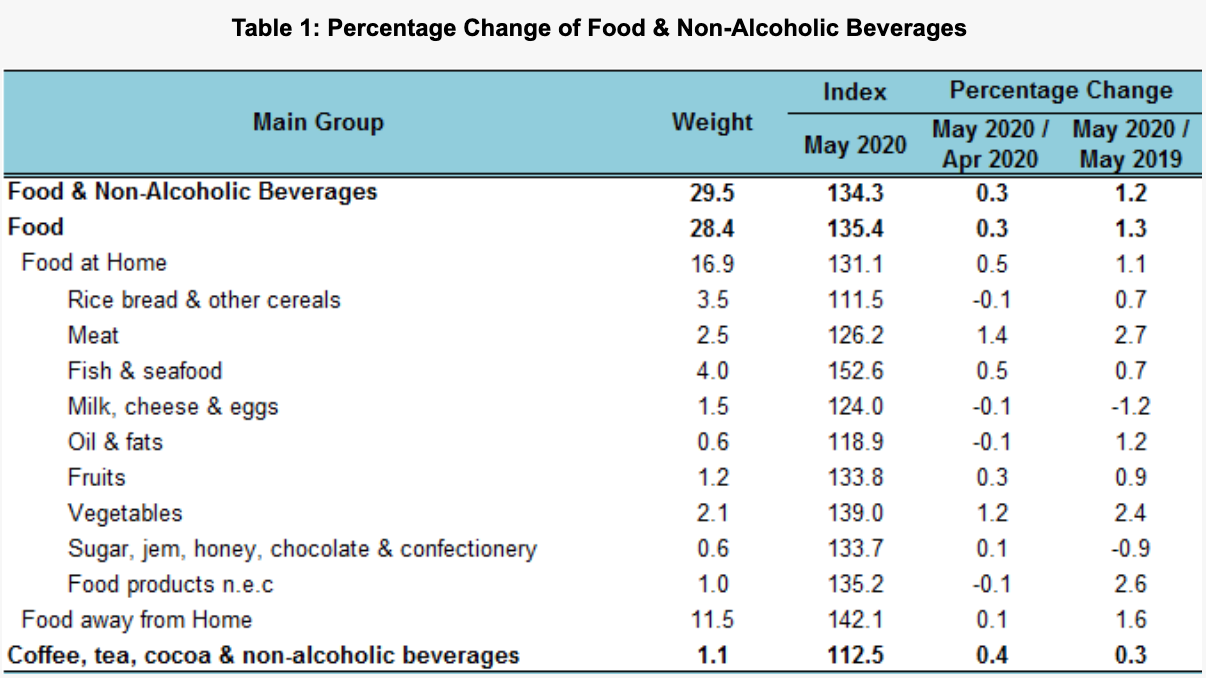

Additionally, food prices have risen nationwide for the third month in a row, according to the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM), with basic ingredients like onions and garlic seeing the greatest increase in price.

Currently, refugees are not recognised as having legal status in Malaysia as the country has not signed the Refugee Convention of 1951.