M'sian Women With Overseas-Born Kids Open Up About Their Struggles For Equal Citizenship

SAYS spoke to half a dozen mothers, who feel deserted by the country they have served and love.

Subscribe to our Telegram channel for our latest stories and breaking news.

Editor's note: The story was updated after the Court of Appeal deferred its decision to 5 August.

In 2016, when Gaithiri Siva — a Malaysian married to an American — found out that she was pregnant, it came as shock, given her medical history. She had been told it would be difficult for her to have a child.

Gaithiri would soon learn that giving birth to her baby was not the only difficulty she would face.

Despite wanting to give birth back home in Malaysia, she could not travel while pregnant as she has struggled with ovarian issues since she was 19, and has had multiple surgeries.

"Given my medical condition and age, it was considered a high-risk pregnancy and I was absolutely told not to travel in my 3rd trimester especially," the 42-year-old woman told this SAYS writer.

The flight she would have had to take would have been over 20 hours.

The investment director ended up giving birth to her baby girl, Asha, in March 2017 in San Francisco, the US, after weighing her options that involved risking not only her life but also that of her child.

A risk, Gaithiri told me, "I wasn't going to take."

At the time, though, she had no idea the uphill battle that lay ahead when it came to passing her Malaysian citizenship onto her newborn child. It's been half a decade since and she's exactly where she started.

Like many Malaysian mothers married to foreign spouses, Gaithiri, too, had not realised just how far Malaysia's gender discriminatory laws go in making women feel like second-class citizens, who are not deserving of the same privilege that's naturally granted to Malaysian men married to foreign women.

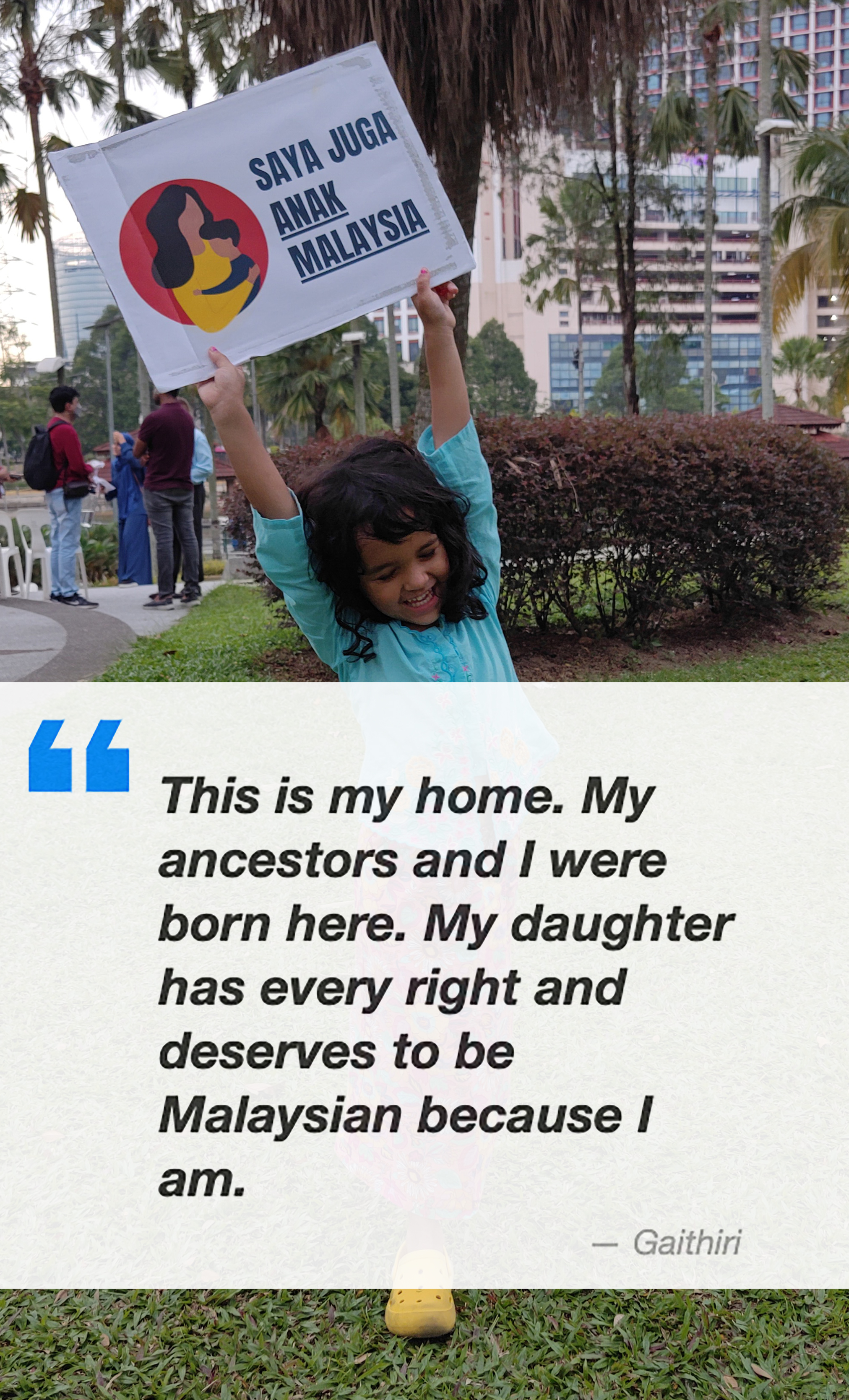

Gaithiri with her daughter, Asha, at an event on Monday, 6 June at Taman Jaya Park, Petaling Jaya.

Image via Gaithiri Siva (Provided to SAYS)This writer spoke to half a dozen such Malaysian mothers fighting to pass their citizenship onto their overseas-born children, the same privilege that Malaysian men with foreign wives automatically have

They fear that they might not see their children become citizens of their home country in their lifetime, and it has only been exacerbated by the death of one such Malaysian mother, whose dream remains unfulfilled.

61-year-old Sabeena Syed Jafer, who was married to a Pakistan national, had been fighting to ensure that her overseas-born children are granted Malaysian citizenship since returning to Malaysia in 2008.

On 29 March this year, Sabeena lost before she could see a successful end to her fight when she suffered from sudden death while getting an angioplasty to treat a blockage in her heart.

"It hurts me to know how close she was to seeing change happen. But didn't get to see it because her government failed her," Niba, Sabeena's daughter, shared during a remembrance prayer for her mother.

"[It's an] unnecessary strain the government decides to put on Malaysian women. [What] if I lose my job, my husband dies or I die, what do [we do then]?" said Christine Nagy, who is married to a British national.

She had to give birth to her daughter in the UK after having suffered two miscarriages.

"I considered giving birth in Malaysia but due to my job and my relatively old age as a first-time mom, I was discouraged," Christine, who is in her 40s, told me, adding that she's frustrated.

Frustrated with the fact that the government — instead of helping — is spending taxpayers' money to fight a landmark ruling allowing Malaysian mothers to pass their citizenship to their overseas-born children.

Christine, who works as a business consultant, does not understand why her own government would not let her have the same rights as Malaysian fathers when it comes to conferring citizenship.

"During the [pandemic] my mother was struggling mentally, I got approval to work remotely but could not bring my child back with me. My daughter asked why she could not come with me," Christine said, adding that she couldn't explain to her that it's because she as a woman does not have the same rights as a man.

I do not want her to feel inferior, but she keeps asking 'why? Why not?'

"[I can't] explain to my child. [I can't] explain to any of my colleagues or friends why I need to make all these trips, and yet my child is still not Malaysian. Also, as my husband has no family in the UK, we would like our daughter to grow up in Malaysia and yet this seems nearly impossible," said the Germany-based mother.

Malaysia is among some two dozen countries including Nepal, Iran, Iraq, Qatar, Bahrain, and Saudi Arabia that prevent women from passing their nationality to their children on an equal basis with men

In fact, Datuk Seri Hamzah Zainudin, the Minister of Home Affairs, denies that allowing only Malaysian fathers to obtain automatic citizenship for their overseas-born children is discriminatory.

High Court judge Akhtar Tahir, who made the landmark ruling, disagrees with Hamzah.

"The discrimination is apparent," he said while ruling that Article 14(1)(b) of the Federal Constitution together with the Second Schedule, Part II, Section 1(b), pertaining to citizenship rights, must be read in harmony with Article 8(2) of the Federal Constitution, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of gender.

The government has since sought leave to challenge the ruling.

The Court of Appeal — which was scheduled to decide on 22 June if the government could appeal against the landmark ruling by the High Court, and continue to deny automatic citizenship to overseas-born children of Malaysian mothers married to foreign spouses — deferred its decision to 5 August.

On 9 September last year, when the High Court affirmed the right of Malaysian mothers on an equal basis with Malaysian fathers, these mothers were "cautiously optimistic". But their joy was short-lived.

35-year-old Esther Teo was "over the moon" after the landmark judgement and told her seven-year-old daughter that she is going to get a Malaysian passport soon "just like her sister". She was devastated when she learned that the government has decided to appeal barely 72 hours later, Esther told me.

"Until today, we still do not understand why the government is still trying so hard to deny our equal rights. This right has been enjoyed by Malaysian fathers since independence," she shared her frustration.

Esther was working overseas when she was pregnant with her first daughter and due to her job commitment at the time, she wasn't allowed to travel back to Malaysia to give birth.

According to her, when she contacted the Malaysian Embassy, she was assured that it won't be an issue and that she just needs to come over to the Embassy and hand over her application.

She told me that she had double-checked with her Malaysian colleagues, too. At the time, though, Esther wasn't aware of just how the citizenship laws of her country would discriminate against her.

Like Esther, Gaithiri, too, was under the impression that the process for her "would be the same as men" as she had Malaysian friends in San Francisco who had Malaysian children with Malaysian passports.

Gaithiri told me, that in hindsight, she realised that all of them were Malaysian men, and while she can't change the past, she does sometimes wonder if she would have made a different decision to give birth here in Malaysia had she known we have this discriminatory practice when it came to conferring citizenship.

"That we are faced with this dilemma and choice of whether to risk our lives to ensure our child is Malaysian — a dilemma and choice no Malaysian man has to face or make — makes this incredibly hard to tolerate and accept," the 42-year-old mother, who is now based in Malaysia, told me.

Gaithiri shared that when the High Court ruling came, she felt seen and was thrilled.

I had hope in my heart for the first time in a very, very long time. It didn't last very long.

Gaithiri, who has been navigating the lack of procedural standards and clarity from the National Registration Department (JPN) — the agency responsible for determining citizenship status — for four years now, learned that there are other mothers who have been waiting longer, some up to 10 years with no news.

"We're at the mercy of the discretion of the officers. And then told just to accept it and live with it," she said, adding that the same hurdles have been in place at JPN despite the High Court ruling.

According to Gaithiri, she and other mothers in similar situations have compared notes, and they essentially get a standard response each time they write in — that citizenship is the highest award granted by the country. And as such, applications for it needs scrutiny and hence will take time.

"So when I write back to ask how I can assist, [like] if they need additional documents — I've never gotten a response," she said, adding, "When we aren't given the same rights as men in this country we are saying that Malaysian women are less worthy and less important than our male counterparts."

And while the Home Minister may claim that allowing only Malaysian fathers to obtain automatic citizenship for their overseas-born children is not discriminatory, Gaithiri and other mothers beg to differ.

"We are 100% Malaysian just as these men, have roles and contribute to the country and society the same as men, and pay the same taxes as men, yet somehow when it comes to conferring citizenship, we are lesser and have to face insurmountable obstacles to obtain citizenship for our children? Of course, it's discrimination," said Gaithiri, who works with a global grassroots-led investment fund.

While the High Court ruling was supposed to make it easier for mothers to apply for citizenship for overseas-born kids, it has had the opposite effect with more hurdles in place, according to the mothers

Take for example Christine, all her attempts to register her four-year-old have been futile.

"[Now] even more documents are required. We applied in January this year and still nothing. The JPN has not given us any reason for still not processing the documents. We check every other week," she said.

Christine is not alone. 42-year-old Rachel Ng has been facing similar hurdles.

Rachel, who is based here in Malaysia, had emailed JPN for a status check on her application for her eight-year-old son born to her Irish former husband but has not heard any response for over three weeks.

"Their phone number is always engaged," she told me.

According to Rachel, she heard from other mothers that JPN has been instructed from "above" to only approve applications for the six mothers in a suit —brought together by the Association of Family Support and Welfare Selangor & KL (Family Frontiers) — that seeks citizenship for overseas-born children.

"I'm not a plaintiff so they [won't] issue. Another reason is the pending Court of Appeal judgement which we will hear on 22 June. So they are waiting to see what the judgement is then act accordingly," she said.

A Family Frontiers spokesperson, in an email to this writer, acknowledged that while JPN has facilitated the issuance of citizenship documents to the overseas-born children of the six plaintiffs, the High Court order clearly states that the decision applies to "all Malaysian mothers in similar circumstances".

"Meanwhile, other impacted mothers who have since submitted their documents have yet to receive their children’s citizenship documents. There is still an absence of procedural clarity and consistency among JPN branches and Malaysian Missions Overseas which we hope will be addressed," the spokesperson said.

The Family Frontiers spokesperson added that many women who submitted their documents have been told that they are required to furnish additional documents not required of men, such as the mother's new birth certificate even though their current birth certificate is valid, a head-to-toe photo of the family, and one mother was even asked for a statement stating that her three-year-old child is not attending school.

We are stuck in limbo. We don't know what to do for our children to live in this country freely.

Like Christine, Rachel, too, had multiple miscarriages before her elder son was born.

"I fell into a [depressive] spell after the miscarriages and was on medication. [During] my whole pregnancy with my elder son, I was very neurotic and I worried constantly. All I wanted was the safe arrival of my baby. So I would never risk my baby's life in flying long haul to come back to give birth," Rachel shared.

The mother of two, whose other son is a Malaysian citizen since he was born here, told me that while the actual application to register her elder son itself was fine, it's the inconsistencies after that are distressing.

"I was told during the application that it would take two years to process. Two years later I was told it would take six years. Now seven years [have passed], still nothing. Every single status check was just a short "pending, you just wait" with no definitive time frame. The yearly visa renewals are tedious and time-consuming. School registration is also tedious and uncertain," Rachel said.

Not every mother may have a "dramatic" story, as one mother put it, but all of them share the same struggles of their precarious situation for seeking the same rights that men are automatically given

36-year-old Patricia Low, who has two kids, aged eight and six, told me that she moved to Ireland when she was five months pregnant as her husband, who is a British national, was offered a position there.

"I was young and clueless and had no idea of Malaysia's gender-discriminatory laws," she said, adding that even if she knew about them, she probably wouldn't have chosen to give birth alone in Malaysia.

I would have wanted my husband to be there by my side as it was my first pregnancy.

The mother of two was in such disbelief when the High Court ruling came in that she cried.

"When you've grown up here, you get used to disappointments and the average folk losing to the higher powers in government. So it was a surprise, but a good one. I cried. I felt seen and the words of the judge in his decision resonated so deeply for all mothers in this situation," Patricia shared with me.

"Each time the government denies and challenges the ruling, it feels like a slap in the face. This country is my home, I am a Malaysian, but I am being told that my children do not belong here. You deny my children citizenship because they were not born on Malaysian soil, but they were born from the womb of a Malaysian mother," she said, adding that there were many times when she felt like giving up.

And this feeling to give up was at its worst on 29 April, right before Raya, when Home Minister Hamzah held a citizenship award ceremony that was streamed live on Facebook, Patricia recounted.

On that Friday, a 22-year-old stateless woman, Rohana Abdullah, who was raised by a Malaysian Chinese mother, Chee Hoi Lan, was granted citizenship. Along with Rohana, 34 applicants, aged between five and 24, received citizenship approval letters. Of them, 18 were male, while 16 were female.

"No mention of us mothers and our long wait for citizenship. While I was happy for these young ones, it felt like salt being rubbed on a wound, like being spat in the face. I felt so low that day and wondered if my children will ever, ever get their citizenship documents," the 36-year-old freelance writer said.

Rohana Abdullah while receiving her Malaysian citizenship approval letter from Home Minister Hamzah.

Image via New Straits TimesThe stress over the repetitive application and renewal process of her husband and children's social visit passes has haunted Patricia since 2017. It has now given her anxiety issues with physical side effects.

"Every Immigration trip means I'm out with a debilitating migraine for the next few days. The emotional hurt from the discrimination. Some mothers are in more precarious situations, it hurts to think how much worse it is for them," Patricia shared when asked about the struggles she has faced due to the citizenship law.

Similarly, the discriminatory law has left 38-year-old Li Li, a divorced mother, overwhelmed.

"The pain and hardship [have] doubled. I have to beg, request, cry, and stress a lot just to renew my kid's passport," the Italy-based engineer told me, adding that in order to have the full custody of her five-year-old daughter she sacrificed many of her rights and had to agree to a divorce by mutual consent.

Like many of the mothers in this story, Li Li, too, suffered a miscarriage during her first pregnancy. And complications from it led to her being bedridden during her second pregnancy, preventing her from flying.

In March 2020, at the peak of the pandemic, when the Malaysian government was repatriating Malaysians in Italy, the single mother wanted to join but had to stay back as her kid was given only 30 days visa.

How to renew and extend a visa in the midst of a pandemic?

And when she tested positive for COVID-19 in December last year, her fear and challenges magnified ten times given her situation as a single mother raising a kid alone with no support system in a foreign land.

Apart from waiting for five years to no avail to see her daughter's application get processed, Li Li also fears the other uncertainty the future holds if her former husband decides to fight back the custody.

Li Li's concerns are echoed by Gaithiri, who considers this a gender justice issue.

"I say gender justice because when we aren't given the same rights as men in this country [...] what message are we sending to our daughters and granddaughters when we do this? It also goes against Article 8 of our Constitution which guarantees gender equality," Gaithiri noted.

Not only that, the gender discriminatory laws of Malaysia, she told me, also strip women of their autonomy and ability to make decisions for themselves and their families.

"Whilst this is not the case for me, many mothers are stuck in terrible situations, in abusive relationships, in fear of losing their child, in having to choose to risk their [lives], and single mothers bearing the brunt of caregiving without support because they aren't able to pass on their citizenship to their children."

For these mothers, it's not about having the same rights as Malaysian fathers for the sake of it. They desperately want their overseas-born kids to grow up in Malaysia as Malaysians, to have the same experience and connection with family and community that they did.

For Gaithiri, she told me that she doesn't want this conversation to become about dual citizenship.

"Because what about the Malaysian men whose children if born overseas automatically receive Malaysian citizenship — why is the dual citizenship issue not raised for them?" she pointed out.

"Without citizenship — she will not have the same access and opportunities as her cousins and peers for education. For public schooling, she will always face a late start each year and she won't be able to participate in many co-curricular activities in school and sports," she said, adding that even for healthcare, they always have to pay more — more than double each time because she isn't recognised as Malaysian.

Back in August 2020, when the borders were closed due to the pandemic, Gaithiri was trying to come back to Malaysia as her dad was diagnosed with end-stage cancer, but her daughter was denied entry.

"My heart shattered at the callousness of the government," she shared.

I honestly felt deserted by the country I had served and loved.

Gaithiri, whose application for her daughter was denied four times only got through when Family Frontiers helped place her story in The Star, appealing to the compassion of the public and the government.

"Essentially, this law strips away any formal recognition that this child is my daughter in this country. And ultimately, it will be that she will feel like an outsider in her own country, and lesser than her peers. I dread and fear what this will do to her mental health and well-being," the mother said while sharing how she deals with the deep anxiety of not knowing what will happen after her daughter passes the age of six.

Meanwhile, Rachel, who is divorced, echoes Gaithiri's sentiments, saying that her own citizenship and nationality as a Malaysian should alone be enough for her child to be recognised as Malaysian.

"I want to raise my children in Malaysia because of my family here. I want them to have the same family values as me, not his father's. And I want them to have a relationship with my family, especially my parents. All this money can't buy and no matter how great the perception of "overseas" is, the other place can give me [the sense of belonging]," she said, adding that it would pain her tremendously to see her sons separated and become strangers if she dies before her elder son becomes Malaysian.

Rachel told me that her elder son has separation anxiety and from time to time he will ask her "am I a Malaysian yet?" and that she sometimes finds his drawings about his citizenship issue.

"I guess that's how he copes," she shared.

Similarly, Esther, who is married to a German national, feels that dual citizenship cannot be used as an excuse to punish Malaysian women when the same argument is not used against Malaysian men.

"[My daughter] was born overseas only due to my job. We are not attached to the country. It is important for me that she is recognised as Malaysian because my whole family is based here," she shared.

Esther's daughter with her drawing depicting her and her mother with the Jalur Gemilang.

Image via Esther Teo (Provided to SAYS)On 5 August, these mothers and many others like them will know if the Court of Appeal provides relief or adds to their precarious situations

If the Court of Appeal decides in the favour of the government, these mothers' fight to overcome the discriminatory citizenship laws will continue at the highest court — the Federal Court of Malaysia.

The Malaysian government could also take into consideration the continued challenges and struggles faced by Malaysian women and keep up with the pledges it makes in the international arena to uphold women's equality and the best interests of children, according to the Family Frontiers spokesperson.

The government can respect the High Court ruling or act on its publicly announced commitment to amend the Federal Constitution to grant Malaysian women equal citizenship rights, the spokesperson said.

As Gaithiri put it, the government has an opportunity to do the right thing here.

"[...] turn your energies to implement rather than block our submissions. That mothers have to fight so hard for our children in this country is shameful and embarrassing," the 42-year-old urged the government, adding that it's time to stop treating Malaysian women and their children as lesser beings in this country.

"I grew up in Kuala Kangsar and then Taiping. My best memories of childhood are in these towns, amidst the amazing multi-ethnic, multicultural communities there. I want my daughter to be able to fully experience the beautiful side of Malaysia, with my family and my community, as a citizen."